Grief Is Political: How to Participate in Activism, Even When Your Heart Is Broken

Grief can make reading hard. Want to listen to this article instead? Find its corresponding podcast episode here.

Grief is exhausting. It’s disorienting. It’s lonely.

And—record scratch—grief is ALSO political.

If that statement made your shoulders tense or your stomach twist—pause for a moment and take a breath. Because this statement isn’t about weaponizing your grief. It’s about recognizing that decisions about who lives, who dies, who gets support, and who is left behind in our society are decisions made in rooms full of politicians, policies, and power.

And if you’re grieving, consider this: Your heartbreak didn’t happen in a vacuum. It happened in a society where the rules—about who deserves compassion, care, safety, and justice—are written by people in office.

You don’t have to have lost someone to war, hate crime, imprisonment, medical malpractice, or poverty to see grief as political. Regardless of how your person died—or even the type of loss that you’re facing (divorce, job loss, and natural disasters are political too!)—your grief is mixed up with politics.

Simply put, in some way, shape, or form, your grief is political!

Let’s talk about it.

What I Mean When I Say “Grief Is Political”

When I say grief is political, I don’t mean it’s partisan. I mean that the systems surrounding death, survival, support, and healing are built by political choices.

In the United States, politics determine:

Who gets access to quality healthcare and who doesn’t, which can be a matter of life or death.

Who is imprisoned or killed by the state—often along dividing lines of race, class, ability, or gender.

Where people live and whether those neighborhoods are safe, financially resourced, and thriving.

Whose bodies and futures are considered valuable and whose are considered disposable.

How we enter into relationships, how separation happens, who gets to initiate those decisions, and why.

Who is forced to flee war or violence and who gets to look away.

Which communities are most likely to lose loved ones early and often and which are most likely to live long, happy lives.

How we travel locally and internationally—and who is considered a risk or threat at the border.

Who is most impacted by changes in climate and how those changes are managed.

How we distribute information about both historical and current events.

Who has decision-making power when we die and when, where, and how those decisions can be made.

And yes—politics also determine how you’re allowed to grieve.

In the U.S., there is no federal right to bereavement leave. Most workers are expected to return to their jobs days—or even hours—after experiencing unimaginable loss. Whether you get time to mourn depends not just on your employer, but on local and state policy, which often excludes families that aren’t “nuclear,” deaths that aren’t considered “close,” and losses that don’t follow a traditional narrative. And that’s just for human death-related losses! As of the writing of this blog, there is no national policy for non-death losses, such as divorce, major diagnosis, pet loss, or natural disaster.

If your grief has ever been dismissed, overlooked, or legislated out of legitimacy—you already know it’s political.

And if this is a new perspective to you, that’s okay too. Take care as you navigate what might be a very big cascade of emotions. Widening your view of grief—and how it shows up in your life—can bring up everything from anger to devastation to shock to despair. Even just seeing differently requires energy when you’re grieving. It’s okay if this feels big. It is.

How to Begin Thinking About Grief and Politics

One of the best ways you can engage with the grief embedded in politics (and the politics embedded in grief) is by asking questions about your own grief experience.

Start by considering:

How was my loss political?

What societal systems or structures had an impact on my grief—positive or negative?

Who, besides my friends and family, might have made decisions about my experience?

Below are a few ways I might apply these questions and view my mom’s death through a political lens. She died from breast cancer in 2013:

Breast cancer research is often publicly funded—i.e. with taxpayer dollars paid to the government—and requires organizations to lobby politicians to put money towards finding treatments and cures. Politicians and people inside the science and research systems were making decisions about whether my mom’s specific type of cancer mattered, and whether or not learning around it was worth funding.

Throughout her diagnosis, treatment, and death, she was cared for by a team of healthcare professionals from Duke University Hospital. Hospitals can be privately or publicly owned, for-profit, or not-for-profit. In researching this blog, I learned that Duke Hospital is a privately owned not-for-profit hospital, which means it’s tax exempt and—in an ideal world—exists with the intention of getting people quality care versus making a profit to enrich shareholders who invested in the hospital’s growth. Politicians and people inside the healthcare system—including insurance companies—were making decisions about what sorts of treatments my mom should receive, how many procedures they should try before telling her there was nothing more they could do, how much to charge for their services, who to hire as doctors, nurses, chaplains, and support staff, and where the line was between treating the disease and calling in hospice.

My mom died at home and her body was removed by workers from our local funeral home. Politicians and people inside the deathcare system were making decisions about how long her body could be with us and how and where it was allowed to be honored after her death.

When she died, I was 21 and on winter break from college, so I didn’t consider something like bereavement leave. But I did return to a college campus that had no system in place for supporting grieving students beyond meeting with an intern therapist who had not yet completed grad school. I had the sense my grief was overwhelming to them and I left therapy after just a few sessions. The college I attended, Appalachian State University, is publicly funded, meaning every choice from our football team to our mental health programs were likely influenced by the desires of politicians at the state and federal levels. Politicians and people inside the education system were making decisions about how much the mental and emotional health of students mattered, when and how to serve bereaved students, and where funding for the counseling center fit in alongside all of the university’s other expenses.

As you can see, my statements about the intersection of grief and politics are not partisan. They’re not disparaging one side while praising the other. They’re simply acknowledging that within the small, intimate experience of my personal grief, a larger influence was at play, constantly making consequential decisions in the background.

My loss, just like yours, took place inside of the bigger system of politics.

How to Get Involved in Politics as a Grieving Person

When you understand that politics and grief are connected, it’s tempting to jump right into the deep end and sign yourself up as a volunteer for everything or subscribe yourself to every possible social media account doing justice work in your area. Suddenly political activism is your other full-time job and your inbox is piling up with reminders of how bad things are—and how you’re a necessary part of making the world a better place.

That’s a fast track to not only activist burnout, but grief burnout too.

As you tend to your mind, body, heart, and spirit while grieving, consider the following questions. Use them as a guide to get started:

What 1-3 issues break my heart the MOST?

Think about how you wish things could’ve gone differently with your own loss or how you could contribute to making future grievers’ lives just a little bit easier. For example, one client of mine lost her transgender daughter to suicide. She is passionate about supporting organizations that help LGBTQ+ folks feel seen, heard, and included—both on an emotional level and on a legislative one. Another client of mine who suffered the loss of a baby became an advocate and spokesperson for the hospital where she received incredible, empathetic care.

What is a reasonable amount of time, energy, or money I can contribute to this cause?

Be SUPER realistic here. If you’re paying off funeral costs or medical debt or if you’re fighting someone in court, you may not have the financial means to support political causes. The tables might be turned if you just received an inheritance from a loved one or downsized your home (and your mortgage payments) after a loss.

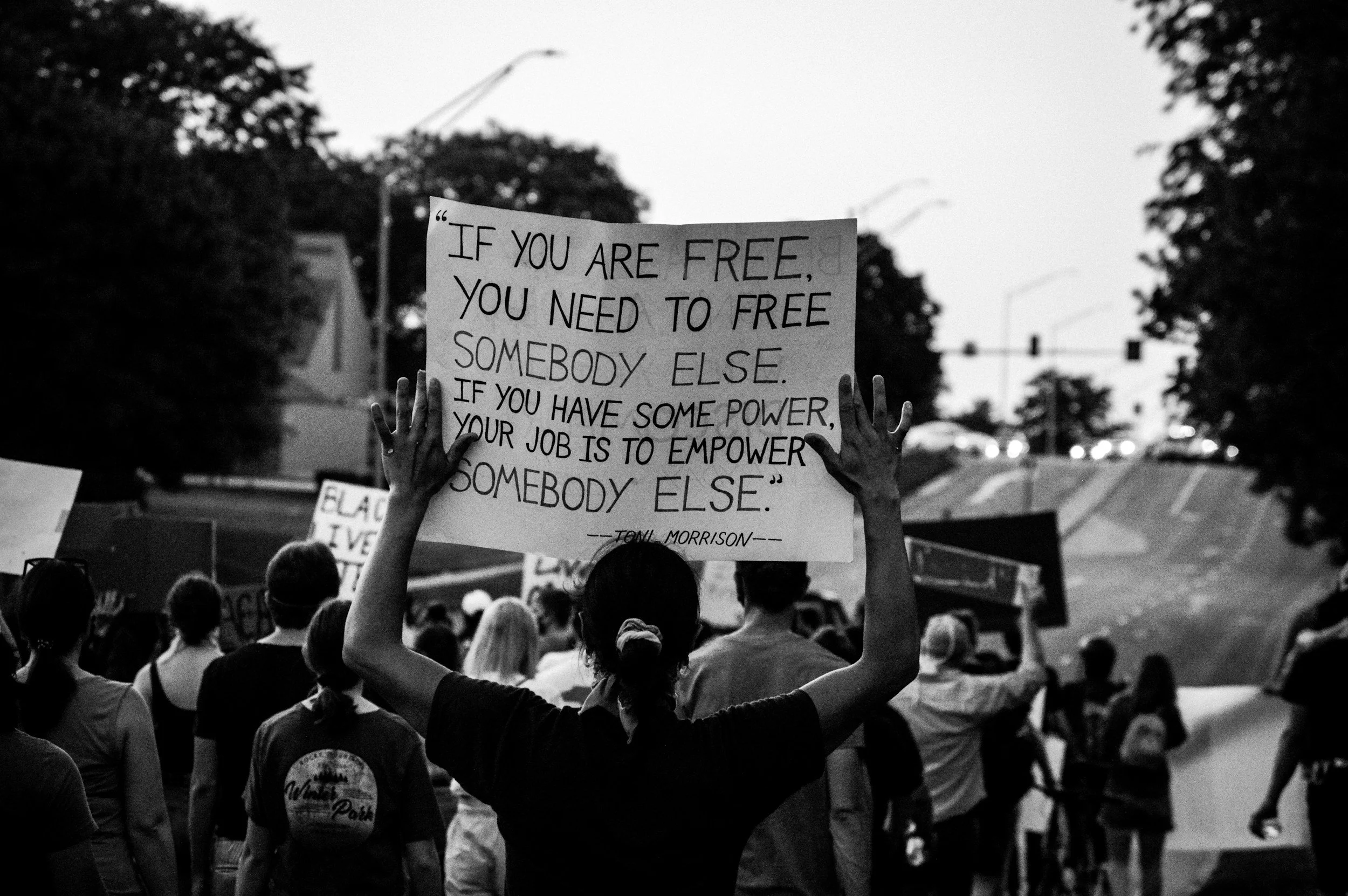

And money is just one aspect of contributing to activism. Consider how much time you might have to volunteer, make phone calls, or send letters on behalf of a cause. You might also have special skills, such as meal planning, graphic design, social media and marketing, or first aid to contribute to an organization in your area. As many in-person demonstrators will tell you, simply showing up with your body during a march or a rally is a great way to send a political message. You are contributing to a cause’s literal numbers—numbers that eventually influence change.

Can I join a movement already in progress?

Speaking of organizations, there are thousands—probably hundreds of thousands—of organizations working for all kinds of political causes. Some grievers I know feel an immense pressure to start a charity or company in honor of a loved one who died, but that is a LOT of work, and I can confidently say it’s not for everyone, especially in the early days of grief.

If you’re feeling a call to plant your grief flag in the ground and participate in activism on behalf of a loved one, it may be worthwhile to see what related causes already exist. As Walter Payton said, “We are stronger together than we are alone.” Many organizations band together over a shared identity or a shared cause (I’m thinking of Moms Demand Action which seeks to end gun violence or Doctors Without Borders, which seeks to provide medical care for people in war or crisis, for instance), and you might begin your activism journey by participating in a group that’s already established. You get to show up and have a voice in a larger movement without having to worry about things like fundraising, payroll, marketing, rent, and basically running a business.

How will I know this type of activism is right for me?

Before you do anything, it can be helpful to picture how you’d like to feel after you’ve begun. Because politics—like grief—is never really “finished,” consider how you’d like to feel mentally, emotionally, physically, and spiritually after you’ve started engaging with it. Of course, there will be moments of heartache and despair. Legal and political change can be frustratingly slow, and at times, it can feel like things are sliding backwards (also sort of like grief!). But by and large, many who call themselves activists say that they want to feel like they are taking on their “fair share” of responsibility to better their communities, leaving a legacy, building connections with others who share their values, or having greater empathy for the people around them. You may want to feel more hope, more power to change broken systems, or simply a sense that you’re doing the right thing.

Ready to dip your toe into the swirling whirlpool of politics and grief?

Below are six easy ways to engage in grief-rooted activism—especially when you have very little energy.

6 Easy Ways to Engage in Politics as a Griever

1. Start by Asking Grief-Informed Questions

Grief activism doesn’t always look like shouting from rooftops or marching in a protest.

Sometimes it sounds like an intimate conversation at the dinner table or a post on your personal social media:

“Did you know there’s no legal bereavement leave in most states?”

“I’ve been emailing my reps about [insert issue]. Have you ever emailed a rep about a cause? I’d love to hear your story.”

“I’m donating to this group in memory of my person. Want to hear about them?”

Every conversation plants a seed. You don’t have to be loud to make waves or influence change. Decisions are made one person at a time.

2. Use Resistbot to Text Your Representatives

This is one of my personal favorites for grief activism, because if you can send a text message, you can take political action.

Resistbot is a free service that lets you email your elected officials directly, using pre-written letters about current issues. You just text the word "resist" to 50409 and follow the prompts.

You choose the issue you’d like to send an email about, select a pre-written letter (you can tweak it if you want), confirm your current zip code, and confirm that you would like Resistbot to send the email on your behalf. You don’t even have to open your Mail app!

This is activism for the exhausted. And it matters. I’ve been using Resistbot since 2016 to share my opinion with my representatives and many times, I’ve even gotten replies from them!

3. Try the 5 Calls App for Easy, Scripted Advocacy

If you want to take it one step further and you don’t mind talking on the phone, 5 Calls is a wonderful app that does all the hard parts for you.

Here’s what it offers:

Phone numbers for your local, state, and federal reps

Issue-based call topics (updated weekly)

Simple scripts you can read word-for-word

According to the creators of the app, “Five calls feels like a manageable amount for most people.” But even if you only make one call to your representative, you’re making a difference. You don’t have to find the right words; you just have to read the screen. You can absolutely add your own perspective—including your grief story—if you like. But it’s not required.

Elected officials report that high call volume is often their reason for voting for something, especially if it goes against their party lines. Saying, “We were inundated with calls from constituents who wanted this bill to go through!” is a very valid reason for making a tough political decision.

If you’d like to think of it another way, I’ll sum up one of my favorite authors and podcasters, Tori Dunlap of Financial Feminist: “Your representatives are working for you! You’re not bothering them when you call. You’re their boss! It’s literally in their job description to make you—their constituent—happy.”

4. Write a Postcard (or a Stack of Them)

There’s something powerful about putting pen to paper. Postcard activism lets you write directly to voters or legislators in short, impactful ways—no technology required.

You can:

Join campaigns or “postcard parties” that send postcards to voters in swing states

Write to representatives about grief-related policy

Help local organizations get the word out about specific causes or events

It’s low-pressure, creative, and you can do it in your pajamas with a cup of tea.

5. Connect with a Local Mutual Aid Group

If the term “mutual aid” is new to you, here’s a quick definition: Mutual aid is a form of community support where people help each other directly, without waiting for institutions or charities.

A local mutual aid group in your area might look like:

Sharing meals with neighbors

Distributing hygiene kits to unhoused people

Providing child care or transportation to grieving families

Donating medical supplies, money, or time

Mutual aid is activism that says: Your pain matters. Your survival matters. And we take care of us.

Most cities and towns have grassroots mutual aid groups you can find via social media or sites like mutualaidhub.org.

6. Make a Donation That Honors Your Grief

You don’t need to have a ton of money to make a meaningful contribution. A $5 or $10 donation—especially in the name of someone you’ve lost—can be its own act of political resistance.

Consider giving to organizations that are grief specific like Evermore, a nonprofit working to shift U.S. policy around grief, specifically bereavement leave after a loss. You could also donate to your local grief support charity or hospice, as organizations like those are often underfunded.

Closing Thoughts: Your Broken Heart Is Not a Barrier to Activism; It’s Your Biggest Political Asset

Grief has this way of cracking us open, of making us see heartbreak, injustice, power, and systems more clearly. If your loss has started a fire in your belly for something to change or a deep longing for a better world, listen to that.

That’s your grief asking you to take action.

And just in case you need to hear it: You don’t need to be “completely healed” from your loss in order to do something. Activism is full of people whose hearts are overflowing with both pain and hope for things to get better.

Grief is political. And you can be an activist while brokenhearted.

You don’t need a megaphone or a protest sign (unless that feels good to you).

You don’t need to run for office or organize your entire city.

You just need to care—and be willing to take one small step in the direction of change.

I get that the world is heavy. I get that you’re exhausted. But I also get that some part of you knows that your grief is more than one loss that happened to you. It’s structural and systemic. And you want to do something about it.

Consider this your invitation. 🗳️