What It’s Like to Look Like Someone Who Died: Grieving in a Familiar Face

Grief can make reading hard. Want to listen to this article instead? Find its corresponding podcast episode here.

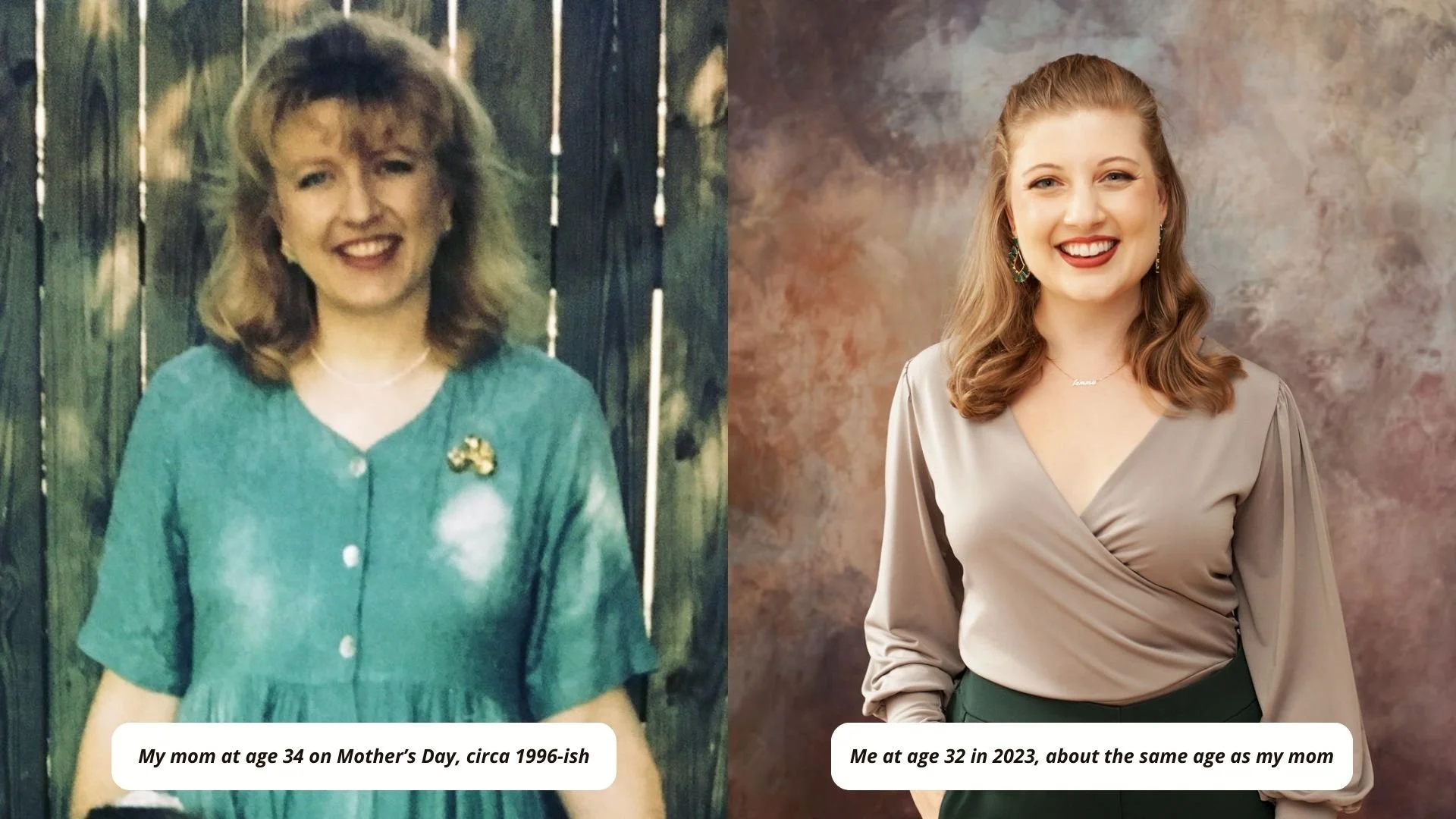

It’s always fun showing somebody new a picture of my mom.

They look at her. Then they look at me. I wait, watching their mental gears turn. They look back at the picture, then back at me and say, “Oh my god. You look just like her.”

Yeah. I do. I look just like my dead mom.

Most of the time, I view mine and my mom’s physical similarities as a compliment. But with the arrival of each fresh milestone—another anniversary of her death, another Christmas, another Mother’s Day—I can’t help but wonder what my life would be like if I didn’t resemble someone who died.

Because the older I get, the more I remember: My mom is dead. And it’s not because there’s something wrong with me or my brain. It’s because the more time passes, the more I inch closer to the 21-year time span where I physically knew my mother—that period between age 30 and age 51.

In other words, the older I get, the more I look like the mother I loved and lost.

Almost every single time I pass a mirror, I think, “What the hell is my mom doing here?”

And then I realize, “My god. That’s me.”

Like many grievers who look like someone who died, my own face is the biggest activator of my grief.

You Can’t Control Resemblance

When I spoke with Cara Belvin, founder of the nonprofit Empower, on my podcast, Grief Grower, she said something similar: “I look just like my mom… and that was triggering for my family. So I was acutely aware of that as I was growing up.”

Cara’s mother, Kit, died of breast cancer when Cara was just nine. She told me that even now, at 48, she walks into rooms and stops people in their tracks.

“It was my mother’s sister, her best friend, my aunt Patty. Her brothers and their wives. My mother’s mother, my Nana Kay. And her best friends. When I’d walk into a room, that would like bring them to their knees. And that will make me cry because I felt bad about that… I felt like I was making them feel bad for many years.”

Looking like someone who died—for better and for worse—is one of many aspects of grief that’s out of your control.

There’s a deep emotional weight in looking like someone who died. You carry the knowledge that your resemblance to them causes the people around you joy or pain or both. You’re basically a walking grief activator for everyone in your midst. Cara put it this way: “It’s comforting and terrifying. [People who look like someone who has died] walk into a room and we remind people of who they've lost. And yet, we are our own individual persons, living our own individual lives.”

Whether people are happy to see you because you remind them of someone they love or people avoid your eyes because they look too much like the eyes of someone who hasn’t been here on earth for many years, your physical appearance has an impact on others around you.

You might hear things like “You look just like X,” or “I feel like I’m talking to X when I talk to you.”

And regardless of whether you receive these statements as blessings or curses, being a dead person’s doppelgänger is something that you carry alongside whatever grief you have for the person who died. It’s an inextricable part of your unique loss experience.

Seeing My Dead Mom in the Mirror—And the Inevitable Questions That Follow

I looked like my mom growing up, but our resemblance is getting eerier as I get older.

As I settle into my thirties, I find myself doing double-takes every time I pass by a mirror or a store window. I’m starting to look just like the mother who raised me… the same one who died twenty one years later.

In milliseconds, I remember her death. Then I simultaneously reckon with my own.

I ask myself things like:

Will I live to see 51?

Will I get breast cancer too?

Will I have to shave my head?

Will I lose my eyebrows?

Will I be lucky and privileged enough to see what my face—and by extension my mom’s face—looks like in old age?

You might be asking similar questions each time you catch a glimpse of your face, wondering about your own death, your own future illnesses, or whether you’ll live to the same age as your person (or even live beyond it).

These questions are normal, especially when you’re greeted with an image of someone who died each time you look in the mirror. They’re an interwoven, inescapable part of wearing a dead person’s face.

Embodying My Mom in Me—From Laughter to Dancing

When my mom’s physical body was no longer a tangible part of my life, my own body became the place where she lived.

Before she died, I casually noticed glimpses of my mom in my facial expressions, hand gestures, and mannerisms. I laughed and she and I would joke about how I would “turn into her” one day.

Since her death, I seek my mom relentlessly in my bone structure, posture, and physical presence. I need her to show up for me through me, and I feel an ongoing desire to call her forth beyond the obvious traits like hair color, eye color, and smile.

I do my best to embody her and remember her by moving and expressing like she did in life. I throw my head back when I “cackle-laugh.” I talk with my hands just as much as I talk with my mouth. I imitate her doing her high school pom pom dance routine when the song “Knock on Wood” comes on—something I used to find incredibly embarrassing as a child but I fully embrace now.

Cara shared something similar:

“As I got older, [I noticed] I was trying to look more like my mother. I realized I was dyeing my hair brown. I was straightening my hair. I was searching, maybe, for people to turn their head when I walked in the room and say, ‘My God, you look just like Kit…’ I really leaned into that. It felt like another way to honor her.”

Today, it’s wicked creepy how similar my mom and I are. I see her in so many elements of me. And don’t get me wrong: I’m not trying to replace her, conjure her up in an artificial way, or impersonate her on any level.

I’m just a 32-year-old girl trying the very best she can to remember her mom who died. And part of remembering who my mom was is accepting who I’m turning into.

You might physically embody a loved one who died by:

Laughing, crying, or relaxing your body just like they did

Dyeing your hair or doing your makeup like theirs

Wearing similar clothing and accessories

Telling jokes and stories of theirs or using catchphrases they often said

Regardless of whether you actually look like your person who died, these are all beautiful ways to embody and carry forward the things you remember about someone you had a loving relationship with. Or, if you never got to meet them in real life—like in the case of a deceased grandparent, a biological parent if you were adopted, or a parent or sibling who died when you were too young to absorb their physical details—these are just a few practices for feeling connected to them in the present.

What If You Don’t Want to Look Like Your Person Who Died?

Not every griever experiences being a lookalike as a blessing. If you share a face with someone who represents cruelty, hurt, or indifference in your family lineage, it can feel like a burden to be physically similar to them.

Some of my clients and students in Life After Loss Academy have said things like:

“I look like my biological father who I never met and never wanted me.”

“I resemble the grandfather who abused me.”

“I look like my mom, and we weren’t on good terms when she died.”

Cara said it best:

“I want to really be sensitive also to some [grievers who look like someone who died]… if the relationship was strained, maybe there's a motivation to not dress like [them] or not look like [them], I understand all of that.”

Here are a few ways to cope when you don’t want to look like someone who died:

1. Speak your truth out loud.

Whether it's to a trusted friend, a therapist, a grief group, or a blank journal page, say it: “I look like someone I don’t want to look like, and it’s painful.” Giving voice to this experience can offer relief—and connection.

2. Name what’s yours—and what’s not.

It can help to list the traits, values, or behaviors you do want to carry forward (if any) from your lookalike—and which ones you’re consciously releasing. This gives you agency in shaping your identity, even inside a body that brings up painful associations.

3. Give yourself permission not to honor them.

Grief can get tangled up with cultural or familial pressure to forgive, reconcile, or remember fondly. If the person you resemble caused harm—whether to you or others you care about—you are not obligated to memorialize them. Grieving them doesn’t require reverence. You can speak ill of the dead, even if just to yourself.

4. Reclaim their features as your own.

That smile? Those eyes? That jawline? Yes, they may resemble someone else in another lifetime—but they also belong to you in this lifetime. Practice saying, “This is my face. My body. My story. My life to live.” You get to redefine what those features mean in your life as it exists now, today.

5. Create visual, symbolic separation.

You might choose to change your hair, style, or the way you present yourself—not out of shame, but as a declaration of self. A haircut, a wardrobe shift, or even a different kind of energy when you enter a room can serve as a daily reminder that you are not them.

6. Consider a ritual for emotional boundary-setting.

You might light a candle and say, “I carry your features, but I do not carry your pain.” You might write a letter to them and burn it. These small grief rituals create space between you and the person you resemble, while affirming your right to exist as your own person.

Closing Thoughts: Being a Dead Person’s Doppelgänger Is Worth Grieving

Consciously and unconsciously I’ve grown into—and am continuing to become—a physical expression of my mom’s memory.

I embody her on purpose as a way of preserving her memory, but it’s also just happening as my body continues to age. Like it or not, my mom’s memory is very much alive and well on my face. And I’m reminded of it every time I meet my eyes in a mirror.

I’m not necessarily sad about it all the time, but it is a constant reminder.

Some days, I wish I knew what it was like to not be wearing my mom’s face. It’s the one aspect of my grief I can’t escape (because reflective surfaces are literally everywhere). And while I don’t go avoiding mirrors and puddles for fear of having my grief activated, looking like my mom is an experience I grieve because—like my mom’s death—it’s permanent and unavoidable.

I suppose when I really think about it, I can say most days I’m okay with looking just like my mom. It’s an unexpected gift to be able to carry her everywhere without having to remember to put on a piece of jewelry or tuck one of her handwritten notes into my wallet. Most days when I miss her, I have the weird grief privilege of looking in the mirror. She’s still there—framed in the glass, just behind my eyes. My face can never call forth the entirety of who my mom was as a person. But it sure is a hell of an illusion.

Whether you look like someone you deeply loved or someone whose presence was complicated—or even harmful—grieving in a familiar face can be an ongoing, emotional reckoning. It’s okay if that resemblance feels beautiful one day and unbearable the next. It’s okay if it makes you laugh, cry, disconnect, or reach for meaning. Your body, your face, your expression are yours to make sense of. And you don’t have to do it alone.

If this resonates with you, I invite you to listen to my full conversation with Cara Belvin, founder of the nonprofit Empower, on my free weekly podcast Grief Grower. Together, we explore how looking like someone who died shapes our identity, memories, relationships, and the grief we carry forward.

This article was inspired by a popular article I published on Medium for Mother’s Day in 2019. I also talked about the phenomenon of looking like someone who died on episode 78 of Coming Back: Conversations on Life After Loss, also published in 2019.