6 Powerful Grief Metaphors That Help You Make Sense of Life After Loss

Grief can make reading hard. Want to listen to this article instead? Find its corresponding podcast episode here.

Grief is often too big, too complex, or too layered for plain language.

When we say “I miss them,” we might mean something like, “I’m trying to figure out how to carry them with me without feeling weighed down.”

When we say, “I’m not sure how I feel,” we might mean something like, “I’m trying to rebuild from a life that loss destroyed and everything feels weird and alien.”

When we say, “I’m having a hard day today,” we might mean something like, “I saw their favorite cereal in the grocery store and it’s agonizing not to have a reason to buy it anymore.”

That’s where grief metaphors can help.

A good grief metaphor doesn’t solve the pain of grief. Instead it translates it into imagery, and sometimes, words. It offers shape, texture, and meaning to something that otherwise feels invisible and overwhelming. Below are six of my favorite metaphors for grief that can help you make sense of life after loss.

The Ball in the Box analogy | Credit: Everything Funeral NZ

1. The Ball in the Box

Popularized by: Lauren Herschel

The “Ball in the Box” analogy went viral in 2017 when Canadian Twitter user Lauren Herschel shared something a doctor had once told her to explain how the pain of loss changes over time.

She wrote:

“So grief is like this: There’s a box with a ball in it. And a pain button… In the beginning, the [grief] ball is huge. You can’t move the box without the ball hitting the pain button. It rattles around on its own in there and hits the button over and over. You can’t control it. It just keeps hurting. Sometimes it seems unrelenting.

Over time, the ball gets smaller. It hits the button less and less, but when it does, it hurts just as much. It’s better because you can function day-to-day more easily. But the downside is that the ball randomly hits that button when you least expect it.

For most people, the ball never really goes away. It might hit less and less and you have more time to recover between hits, unlike when the ball was still giant. I thought this was the best description of grief I’ve heard in a long time.”

Lauren’s Tweets resonated with thousands, including therapists and grief educators, for its visual clarity and emotional accuracy.

She even wrote a follow-up Tweet about how she’s using the Ball in the Box analogy to talk about grief with her stepdad:

“He now uses it to talk about how he’s feeling. ‘The Ball was really big today. It wouldn’t lay off the button. I hope it gets smaller soon.’”

Why it helps: The Ball in the Box metaphor validates the nonlinear annoyingly surprising nature of grief. Painful moments and sneak attacks that show up seemingly “out of nowhere” years later aren’t setbacks—they’re just the ball hitting the button again.

You can find Lauren on Twitter.

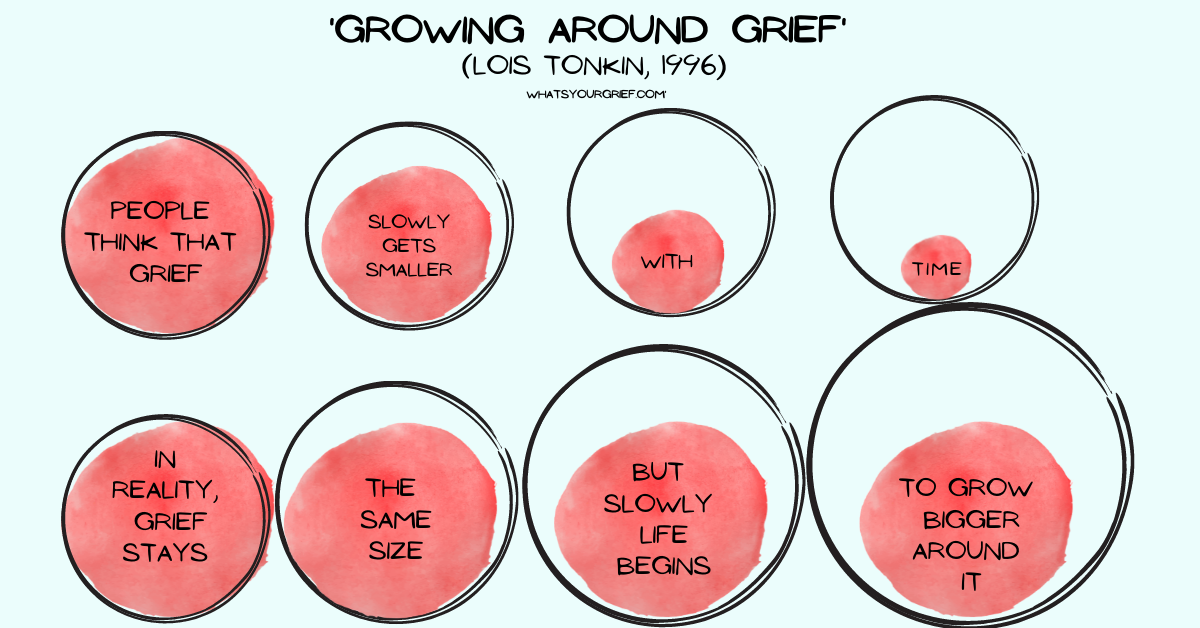

The Growing Around Grief model, created by Lois Tonkin | Credit: What’s Your Grief

2. Growing Around Grief

Created by: Dr. Lois Tonkin

Originally published in 1996, Lois Tonkin’s model of “growing around grief” challenges the common belief that grief shrinks with time. Instead, she suggests that grief stays the same size—but your life grows around it.

After speaking with a grieving mother, she sketched two circles: one showing grief overwhelming life, the other showing life expanding around a still-present grief.

This model has since been illustrated countless times online—including a popular bookshelf version by grief artist Cherie Altea, showing grief as one enduring book on a shelf that slowly fills with other volumes over time. This is one of my favorite interpretations of how our lives can become fuller and richer after loss.

Cherie Altea’s Instagram post about growing around grief | Credit @thejarofsalt

Why it helps: The Grow Around Grief model helps you release the pressure to “move on” or “let go” of grief and reminds you that you don’t outgrow grief—your life expands around it.

Lois Tonkin died in 2019. You can find grief posts and resource on her Facebook business page and and read her book Motherhood Missed: Stories from Women Who Are Childless by Circumstance, which is still in print.

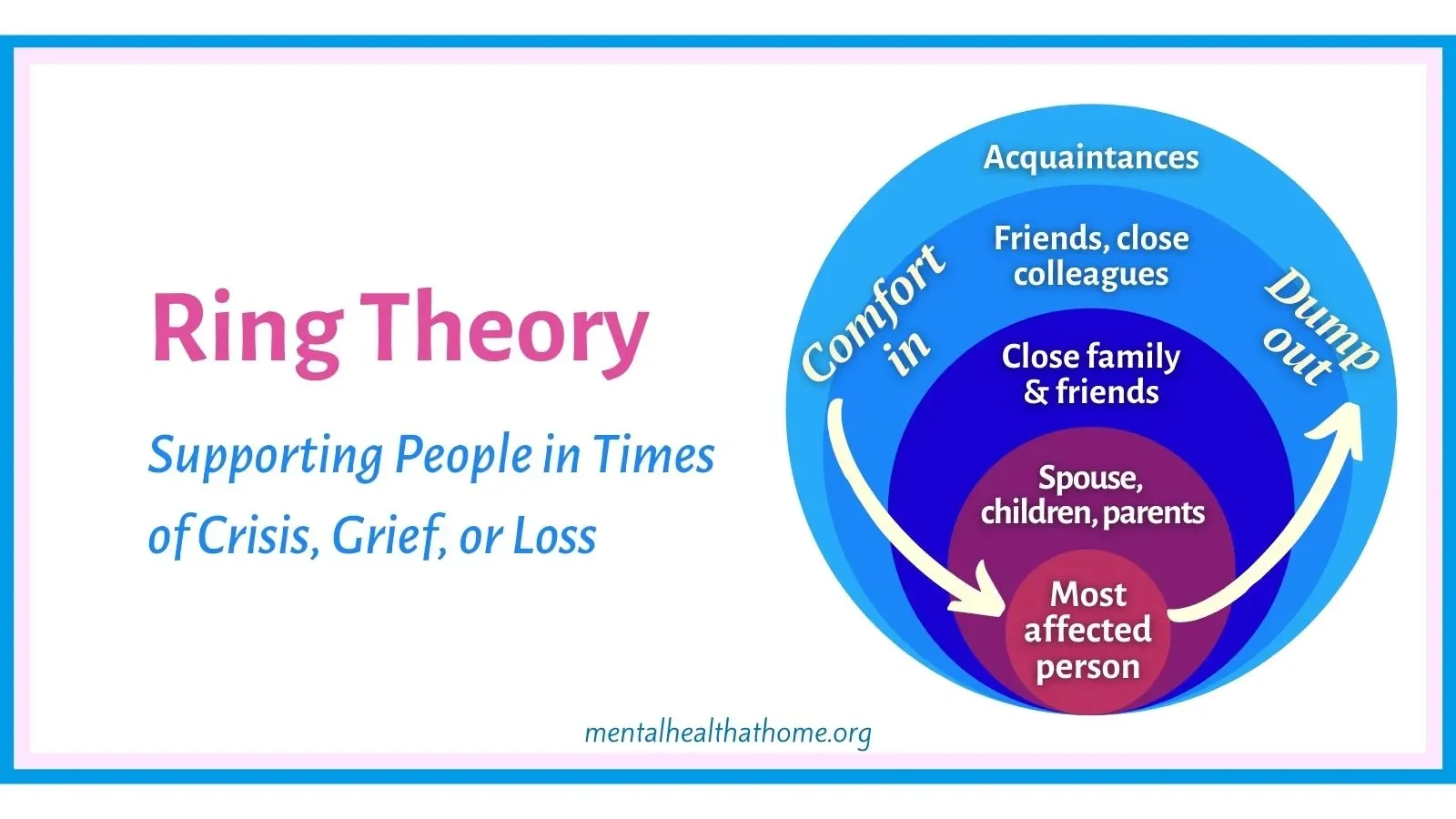

The Ring Theory of Support | Credit: Mental Health at Home

3. Ring Theory of Grief Support: Comfort In, Dump Out

Created by: Susan Silk and Barry Goldman

In 2013, The Los Angeles Times published an opinion piece called “How Not to Say the Wrong Thing.” Written by Susan Silk and Barry Goldman, it introduced the concept of Ring Theory for supporting someone going through grief or crisis.

Basically, if you imagine concentric circles, the center of the circle is the person most directly impacted by the crisis or loss. The next ring includes immediate family or close friends. The outer rings hold acquaintances, coworkers, or more distant connections.

The rule? Comfort in, dump out. You support people in rings closer to the center than you. And you seek your own support from people in rings further out from your own.

For example, it’s inappropriate for a cancer patient’s coworker to look to the cancer patient for emotional support regarding their cancer diagnosis. That coworker should lean out for support from other coworkers, their own circle of family and friends, and helping professionals who have no connection to the cancer patient.

This metaphor is less about how to survive the pain of loss and more about how others should respond to it.

In the article, Susan and Barry wrote:

“The person in the center ring can say anything she wants to anyone, anywhere. She can kvetch and complain and whine and moan and curse the heavens and say, ‘Life is unfair,’ and ‘Why me?’ That’s the one payoff for being in the center ring.

Everyone else can say those things too, but only to people in larger rings.

When you are talking to a person in a ring smaller than yours, someone closer to the center of the crisis, the goal is to help. Listening is often more helpful than talking. But if you’re going to open your mouth, ask yourself if what you are about to say is likely to provide comfort and support. If it isn’t, don’t say it. Don’t, for example, give advice. People who are suffering from trauma don’t need advice. They need comfort and support. So say, ‘I’m sorry,’ or ‘This must really be hard for you,’ or ‘Can I bring you a pot roast?’ Don’t say, ‘You should hear what happened to me,’ or ‘Here’s what I would do if I were you.’ And don’t say, ‘This is really bringing me down.’

If you want to scream or cry or complain, if you want to tell someone how shocked you are or how icky you feel, or whine about how it reminds you of all the terrible things that have happened to you lately, that’s fine. It’s a perfectly normal response. Just do it to someone in a bigger ring.

Comfort IN, dump OUT.”

Why it helps: The Ring Theory of Support sets clear relational boundaries with everyone involved in a loss or crisis situation. It makes it so that grieving people don’t have to manage others’ emotions, and supporters know where to offer comfort instead of unhelpful advice or emotional unloading.

Susan Silk is a practicing clinical psychologist in Michigan. Barry Goldman is her friend and the author of The Science of Settlement: Ideas for Negotiators.

The illustration of Grief as Butter in Pastry | Credit: @ohtruth

4. Grief as Butter in Pastry

Created by: Ruth Chan

After a series of personal losses including the death of her friend Steve, cartoonist and author Ruth Chan created a simple-yet-stunning visual metaphor comparing grief to butter in laminated pastry dough.

As Ruth writes in her comic:

“Grief from loss is like the butter in a puff pastry. It’s huge and imposing and seemingly impenetrable. But eventually it gets folded in. It’s never gone, but instead infiltrates every part. Until one day, it is simply part of you in a way that feels okay.”

Why it helps: It reframes grief as integrated. Not removed or separated from who you are—but baked in, like a croissant. It’s always there, shaping the texture of your life, even when you can’t see it directly.

You can read Ruth’s original Instagram post about Grief Butter here, as well as her follow-up to the original comic here.

Illustration of grief’s weight over time | Credit: Mari Andrew

5. Grief as a Heavy Sack… Then a Briefcase… Then a Purse

Created by: Mari Andrew

In 2018, illustrator and author Mari Andrew created a doodle about grief, showing the weight of grief diminishing over time. First, grief appears as a huge burlap sack—unwieldy, scratchy, hard to carry. Then it becomes a briefcase—still heavy, but easier to move around in the world with. Eventually, it’s a purse. It’s still there and it’s still important. But it doesn't weigh you down the way it did before.

In 2022, she shared the illustration again in a Substack piece about the 7-year death anniversary of her father titled, “Grief Baby,” where she wrote:

“Jumana and I talk from time to time about our ‘grief babies.’ I can’t remember where we got that term, but we’re referring to the length of time since our respective parents died, acknowledging their absence as a presence.

I still vividly remember my grief's newborn stage, when I was sleep-deprived and had no idea what I was doing. Something was screaming at me most hours of the day, and I was completely ill-equipped to understand its wants and needs. After all, I’d never done this before.

When a year passed, I felt a significant internal shift that I misinterpreted as the end of grief. “All done,” I thought. Only to find that the next morning, I woke up with a one-year-old who still needed my attention.

If we rethink of grief as a living, growing thing with a heart and mind of its own, then we can more wholly accept its whims, its mood swings, its occasional vacations away, and its inevitable returns—often when we least expect it.

‘Grief: You’re doing it wrong’ is how I felt so many times during those first confusing years when I hadn’t a clue how to settle this mysterious toddler’s tantrums. Just like dealing with a two-year-old, nothing about the grief baby’s temperament followed any logic.

The grief baby has gotten a lot more complex through the years. Tidy answers aren't going to work on a 7-year-old; a child that age starts questioning the Easter Bunny and demanding a few more whys after 'Because I told you so.'

This 7-year-old is skeptical: No one has any way of knowing any of that.

But this 7-year-old is also imaginative: If there are no answers here, then I can make this experience all my own.

I can traipse around New York alongside my dad's ghost and envision that we are having coffee (and a completely different relationship) at his old haunt in the West Village, I can get upset while waiting for the subway let the pain swoosh me around like a gust from the train, I can use this death anniversary to be sweet to myself or I can use it to listen to his music at full blast or I can use it to feel really really sad. I can live the questions of grief, as Rilke instructs, and children do naturally, rather than force a solution.”

Why it helps: The sack-to-purse illustration helps visualize grief’s evolution as you navigate life. Yes, your grief may always exist—but your relationship to it can become more manageable, familiar, and even imaginative over time.

You can find Mari Andrew’s Substack, books, and art prints on her website.

Some of the dressing room illustrations from my book, Permission to Grieve | Credit: Shelby Forsythia

6. Grief as a Dressing Room

Created by: Me, Shelby Forsythia

In my first book, Permission to Grieve, I used the metaphor of Grief as a Dressing Room to describe how our identity shifts after loss. When you experience a death, breakup, or major diagnosis, your sense of identity is often upended. Who you were may no longer feel accessible. Who you are becoming might feel unknown.

That’s why I often choose to see grief as a dressing room—a private space where you try on beliefs, routines, boundaries, coping tools, and ways of being to see what fits now, in your life after loss.

Some identities feel completely wrong. Some surprise you. Some you keep for a season and replace later. It’s all part of reclaiming your life post-loss—and learning how to live in a new version of yourself.

In Permission to Grieve I wrote:

“Try imagining your identities as articles of clothing in a dressing room. Maybe ‘caregiver’ is a purple sweatshirt, ‘creative’ is a pair of bedazzled jeans, and ‘reliable’ is a cozy pair of grey sandals. These identities make up a part of how you show up in the world, but they are not you. You can try them on (keepers), hang them up on the rack as possibilities for later (maybes), or give them back to the dressing room attendant (definite nos). Grief forces you to outgrow old identities—maybe ‘caregiver’ no longer fits, ‘creative’ is temporarily out of stock, and ‘reliable’ has a bunch of holes in it.

Loss makes it so that some of your identities will never fit again (for instance, ‘religious’ or ‘innocent’), but much of the time, your former identities just aren’t appropriate right now. I can’t tell you how many of my former identities I’ve rediscovered in the past few years that suit me again. It’s like I needed to wait for life’s dressing room attendant to get my size back in stock or—what’s even more fun—realizing that my old identity of creativity is no longer a pair of bedazzled jeans, but a colorful green hat! I had been looking for creativity in its old form, except loss made it so that old form didn’t fit me anymore. But it turns out creativity does still exist—it just fits me differently now that loss has changed my life.

So what do you do if you don’t know what identity to wear? Start with what you know for sure. This could be as simple as your name, height, eye color, age, or geographic location. Then expand to include other definite identities in your life. Is your job title the same? What about your role in the household? Are there any community or volunteer roles that align with who you are now? What about hobbies, talents, or spiritual pursuits? These identities might feel small in the grand scheme of things. Eye color isn’t all that influential in determining your future post-loss, but it is something solid you can keep wearing, and that matters when you’re grieving. Know, too, that it’s okay to wear a bathrobe that has big, bold letters spelling out “I DON’T KNOW” emblazoned across the back. This outfit won’t be your forever attire, but if ‘I don’t know’ is true for you, it’s the identity you have permission to wear right now.”

Why it helps: Seeing grief as dressing room makes space for uncertainty, experimentation, and trial-and-error. It tells the truth: rebuilding is never linear—it’s always changing. And while you can’t always choose what identities are available to you, you have the power to try out the identities or practices you do have control over as you figure out what fits you in life after loss.

Closing Thoughts: Metaphors Help Us Understand Grief in a New Way

Metaphors can’t erase your pain—but they can give it shape. They can help you tell your story, explain your heartache to someone else, or feel seen when it feels like no one gets you.

To be clear, these grief metaphors aren’t about “fixing” you; they’re about validating you. Whether that’s helping you name the unnameable or offering just a little more clarity in a world that’s been blown apart by loss.

If one of these metaphors gave language to your experience, I hope you take it with you.

And if you'd like even more helpful frameworks, tools, and illustrations for coping with grief, you’re always welcome to join us in Life After Loss Academy, my online course + community for grievers.

You get instant access to a video library of short step-by-step lessons for navigating life after loss plus weekly group coaching calls with me. The replays are available immediately if you can’t attend live, and you can cancel your membership at any time.

Here’s a review from a Life After Loss Academy student about finding the words to express her grief:

Life After Loss Academy is open year-round. Join today, or, if you’d like a free “taster” of how the course works and a preview of what you’ll get inside, watch my free workshop!

Click here and I’ll send it to your email.